Risks are part of every project and no amount of planning can anticipate every contingency. Risk management, a major component in any project management education program, is the systematic identification, monitoring and mitigation of risks so that projects have the best chance of success. Risk management education has traditionally been taught in a classroom setting, but this method can be expensive, slow and rigid. Business games - interactive learning environments in which players explore all the components of a complex situation - are a simple and efficacious alternative.

Keywords: Game, project risk management, Simsoft

Introduction

Risk management is one crucial component in project management, but it is a difficult concept for students to master. We have found that students are often unable to relate the theoretical aspects of risk management to real situations or projects. In order to achieve effective teaching and learning goals, scenario-based risk management teaching methods are needed (Carroll, 2000; Rahat & Peter, 2005). Our premise is therefore that theories and practice can be integrated together as scenarios to illustrate the risk management process.

This paper reports on the preliminary stages of a project to design and develop a game that can be used to teach students about some of the dynamic aspects of project risk management. Based on a scenario developed from a real land development project, students must apply project risk management processes. They identify different risk events during the each phase of the project, analyse these risks and develop risk responses. To guide the students, the game provides feedback as decisions are made, and at the end of the game, they have a chance to reflect on their decisions. Pre- and post-game questionnaires will be used to assess Simsoft's effectiveness so that improvements can be made based on users' experiences.

Literature review

To play a game, "is to engage in activity directed towards bringing about a specific state of affairs, using only means permitted by specific rules, where the means permitted by the rules are more limited in scope than they would be in the absence of the rules and where the sole reason for accepting such limitation is to make possible such activity" (Suits, 1967, p. 148). This classic definition contains the key elements common to all games:

- A goal or objective: a "specific achievable state of affairs" (Suits, 2005, p. 186), such as crossing the line first, scoring the most points, or having the best hand. Goals or objectives differentiate games from other types of play. For example, if a game doesn't have a goal "but is something that can be just played with in many way depending on your whim, you have what they refer to as a toy" (Prensky, 2007, p. 120).

- Means: the legal or legitimate ways of trying to achieve the goal or objective of a game. Using a weapon in a boxing match is one way of achieving the goal of downing an opponent, but it is, of course, illegal (Suits, 2005, p. 187).

- Rules: the legitimate means of achieving the goal of a game. Often, rules gratuitously prohibit the most efficient means of reaching a goal in order to make a game challenging and engaging (Suits, 2005, p. 187): a golf ball could simply be placed in a cup; instead, it must be hit from a distance and played from where it lies along the way.

- Lusory attitude: a free-willed acceptance by players of the conceit created by seemingly arbitrary rules simply in order to participate in the game (Costikyan, 2005, p. 195; Prensky, 2007, pp. 123-124; Suits, 2005, pp. 188-189).

In summary, Suits offers a portable version of a game: "the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles" (2005, p. 190).

Games naturally come in many forms. In an authoritative work in the field, Man, Play and Games, Caillois (1961) proposed a classification that depends on whether the role of competition (agôn), chance (alea), simulation (mimicry), or vertigo (ilinx) is dominant. Agoôn are those games "that would seem to be competitive... like a combat in which equality of chances is artificially created in order that the adversaries should confront each other under ideal conditions" (Caillois, 1961, p. 14). Football, billiards, or chess fall into this category. Alea are games of chance such as roulette or a lottery; games of mimicry involve the players becoming other characters, such as cowboys and Indians; while ilinx are "those which are based in the pursuit of vertigo and which consists of an attempt to momentarily destroy the stability of perception and inflict a kind of voluptuous panic upon an otherwise lucid mind" (Caillois, 1961, p. 23).

The game that this research project is concerned with are a subset of Caillois's ag™n classification and they use an adjective - serious - to show they want for more than simple amusement and that they are designed to educate, train, or inform their players (Abt, 1970; Michael & Chen, 2005; Schrage & Peters, 1999).

Teaching and learning framework

The game design was based on the cause-and-effect decision-making framework in Figure 1, which embodies three main ideas: a project risk management methodology, a pedagogical design and assessment, and a simple game.

Figure 1: The project's decision-making framework

Project management methodology

The scenario developed for the game is based on a project framework defined in the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) (Project Management Institute, 2006). According to the PMBOK, a project lifecycle has five phases:

- Project initiation: Defines and authorises the project or a project phase.

- Planning - Defines and refines objectives, and plans the course of action required to attain the objectives and scope that the project was undertaken to address.

- Execution: Integrates people and other resources to carry out the project management plan for the project.

- Monitor and control: Regularly measures and monitors progress to identify variances from the project management plan so that corrective action can be taken when necessary to meet project objectives.

- Closure: Formalises acceptance of the product, service or result and brings the project or a project phase to an orderly end.

Risks can occur in any phases. Game scenario will embed risks in each phase and students will identify, analyse and manage risks

Risk and risk management

Risk refers to something bad that could happen (Hubbard, 2009). Risks are present in all projects, whatever their size and complexity and whatever industry or business sector. This leads to the need to apply project risk management, which consists of the following processes (Standards Australia, 2009).

- Context - Risk management defines internal and external factors to be taken into account when managing risk. This sets the scope for the following risk management stages.

- Risk identification - This stage involves identification fo the potential risk events - what, why and how things can go wrong - that may affect the successful attainment of project objectives. Risk identification should culminate in a list of risks that then need to be assessed.

- Risk assessment (analyse and evaluate): Once project risks have been identified, the next step is to evaluate them in regards to their potential consequences and probability of occurrence. These risks are then ranked to identify management priorities

- Risk treatment: Once the project risks have been identified and assessed, then suitable strategies have to be adopted to cope with them.

- Implementation and control: The selected strategies must be implemented, monitored, controlled and reviewed.

Before the game starts, students are asked to fill in pre-survey which includes five questions about project risk management. This survey is used to test students' existing knowledge on project risk management. The game starts with project background description which provides information about project objectives, background, milestones, time and location etc. Once students understand this background, they enter the project management phases, such as project initiation. Project stage descriptions are provided at the beginning of each phase. Students are required to answer multiple-choice or short answer questions in each of the four stages. Afterwards, immediate feedback is provided to students to show them whether their answer to a question is correct or not, and why. Based on their answer, students can gain or lose money and obtain a score illustrating their learning progress. The student who has highest score is the winner of the game. A small prize, such as a chocolate bar, will be awarded to them. A project stage report is provided to students at the end of each phase. Students are also provided a final report, which records their activity log and feedback. A post-survey is used to test their learning performance and to obtain their perception on game design and usability. Through this, we can continually improve the game (See Figure 1).

By the time they come to play Simsoft, students will have covered the project risk management processes in class and will have detailed risk management notes and templates that they can refer to during the game session.

Pedagogical design and assessment

In general, learning objectives are statements that describe the knowledge, skills and attitudes that students should take away from any particular learning process. This project used Bloom's (1956) cognitive taxonomy to help formulate the learning objectives (see Table 1).

Teaching methodology

The students work individually or in pairs. Based on the starting scenario of the game, information provided during the game, and their own real-world experience, the teams make decisions about how to proceed - by deciding what risk event is relevant for the current stage of the project, what the likelihood is of the risk eventuating, and what the consequences of the eventuated risk may be. Based on the teams' responses, the game provides a commentary on whether the risk decisions were good or bad and the reasons why. The game is now in a new state which the players must interpret from the project reports the game provides. A fresh set of decisions is entered and the life of the simulated project continues.

Table 1: Learning objectives of the game compared to Bloom's cognitive taxonomy

| Bloom's Taxonomy | Learning Objectives for Simsoft |

Knowledge: remember previously-learned materials by recalling specific facts, terminology, theories and answers

Comprehension: demonstrate an understanding of information by being able to compare, contrast, organise, interpret, describe, and extrapolate. | Objective 1: to describe the process of the project risk management.

Students understand concepts of project risk management.

Simsoft engages students in active learning and facilitates their understanding of the value and challenges in risk management. |

| Application: use previously-learned material in new situations. | Objective 2: to apply the project risk management knowledge and skills in the scenario provided.

Students apply the knowledge and skills they learned in the lecture and game to manage specific risks in the designed scenario.

Simsoft allows students to gain hands-on experience from real life scenario and interactive feedback provided by lectures. |

Analysis: decompose previously-learned material into parts in order find patterns and to make inferences and generalisations.

Synthesis: use existing ideas in different ways to create new ideas or to propose alternative solutions.

Evaluation: judge the validity of ideas or information with a certain context. | Objective 3: to assess students' own answers based on established criteria.

Students take more responsibility for their own learning to evaluate their own answers and reflect on how a risk should be managed and what has been achieved in the survey. |

| Objective 4: to skills of effective interpersonal communication and collaboration skills.

Students work as a pair to learn from each other and develop communication and teamwork skills during game sessions |

The game is overseen by a tutor whose role is to:

- Explain the learning objectives to the participants. The participants will be made familiar with the decision-making environment created by the game, the type of decisions that will be required, and the quantifiable indicators of effective decision making.

- Provide the participants with feedback and technical assistance during the decision rounds.

Assessment

Assessment is one of the most important aspects of the teaching and learning process: it can reinforce and enhance students' learning, place students in a rank order, and give a licence to subsequent assessment (Sadler 1989, 77). For this project, summative and formative assessments will be used.

- Summative: students' performance was evaluated based the project cost and overall game score. The project was started with a budget, which could be drawn from or added to based on how the students responded to particular risk events. The aim of the game is to complete the project with the highest possible score and with most of the budget intact.

- Formative: after the students enter each risk management decision, immediate feedback will be provided about whether the decision was correct or not, and whether it was the most appropriate choice if there are number of possibilities. Students will be asked to reflect on their decisions and the feedback before moving on the next phase of the project.

Table 2 summarises the assessment methods, types and corresponding learning outcomes in this paper.

Table 2: Assessment methods, types and learning objectives

Assessment

methods | Description | Assessment

type | Learning

objectives |

| Learning or activity logs | The game has a tool to record all the learning activities and assessments for students and generate a final report at the end of the game for students' self-reflection. | Formative | Objectives 1, 2 & 3 |

| Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs) | This method is used to test students' risk management knowledge and skills. Immediate feedback is provided to students on why their choice is correct or incorrect and which one is correct answer. How much score and money they can gain from this decision. | Summative and formative | Objectives 1, 2 & 4 |

| Questionnaires and report forms | Structured and open-ended questions are developed to evaluate student's learning performance after a game session. These questions focus on risk management content, game design and their profiles. | Formative and summative | Objectives 1 & 2

|

| Short answer questions | These questions are designed for measuring analysis, application of knowledge, problem-solving and evaluative skills. Immediate feedback is provided to students to improve their learning. | Formative | Objectives 2 & 4 |

| Self-assessed questions | They are open-ended questions. Students are asked to assess their short answer questions in a designed online survey after they finish the game. | Formative | Objective 3 |

Game implementation

The game will be run during the first semester of 2012 in tutorials for:

- GIS Management 381/581 (10722/12452) units with 20-30 students.

- Risk Management 641 (10898) unit with 50-60 students.

Before the game sessions, the players will complete an online survey to gauge their knowledge of general risk management and project management principles. After the game sessions, the players were asked to complete another online survey to gather basic profile data (industry experience, any previous experience playing serious games), the players' perceptions of the value of the game helping to understand some of the dynamic complexities of project risk management, and to assess what they might have learned during the game. Post-game surveys are a common feature of game research (Eldredge & Watson, 1996; Faria, 1987, 1998; Faria & Wellington, 2004; McKenna, 1991) so there were many exemplars to draw upon.

A descriptive and statistical analysis of the data will follow.

Simsoft implementation

Simsoft is implemented as a simple Java application (Figure 2 shows the initial screen) and made available through Blackboard. Students could download it to their PC and run it as many times as needed.

Figure 2: Simsoft welcome screen

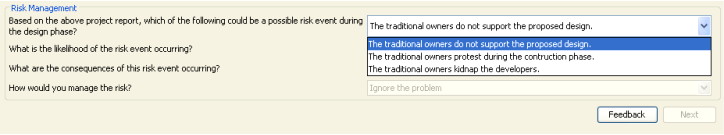

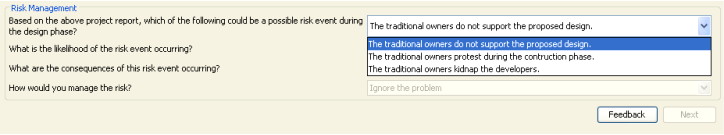

Simsoft follows a wizard design pattern (Tidwell, 2005, pp. 42-44) in which the player is stepped through the phases of the project in sequence. At each phase, the player reads the latest project status report and considers what action to take. For example, in Phase One - Planning, Approvals, and Design, the players first have to decide which of a set of possible risk events are likely to occur (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The possible risk events during Phase One of the project

There is only one option that makes sense: that the traditional owners do not support the project. The second option is relevant only during the construction phase and the third option is unrealistic; if the players select these options, they receive feedback about why their choice is incorrect.

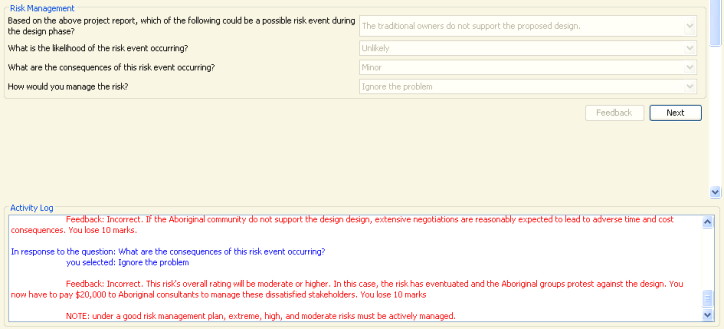

The players next need to assess the likelihood of the risk event occurring (almost certain, likely, possible, unlikely, or almost impossible), what the consequences might be (catastrophic, major, moderate, minor, insignificant), and how they will manage the risk if it occurs (ignore the problem, consult and negotiate with the traditional owners, or terminate the project). Based on the responses, immediate feedback is shown in the activity log.

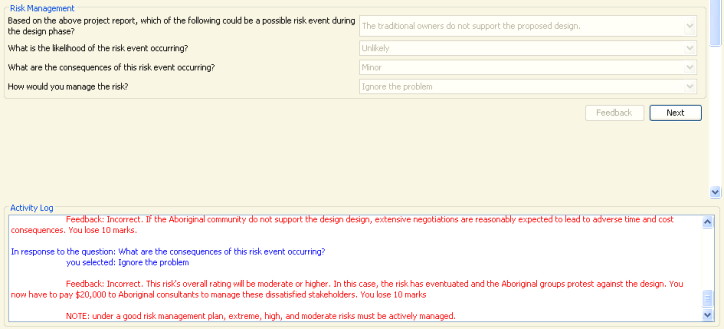

Figure 4: The feedback provided for a set of decisions made in Phase one of the project

For example, in response to the selections in Figure 4, the activity log recorded the following feedback:

In response to the question: "Based on the above project report, which of the following could be a possible risk event during the construction phase?" you selected: "The traditional owners do not support the proposed design."

Feedback: Correct. You score 10 marks. Please continue on to evaluate the likelihood and consequences of this risk event and choose possible methods to manage this risk.

In response to the question: "What is the likelihood of the risk event occurring?" you selected: "Unlikely".

Feedback: Incorrect. As this is a culturally sensitive project, you would reasonably expect a strong likelihood of some problems. You lose 10 marks.

In response to the question: "What are the consequences of this risk event occurring?" you selected: "Minor".

Feedback: Incorrect. If the Aboriginal community do not support the design, extensive negotiations are reasonably expected to lead to adverse time and cost consequences. You lose 10 marks.

In response to the question: "What are the consequences of this risk event occurring?" you selected: "Ignore the problem".

>Feedback: Incorrect. This risk's overall rating will be moderate or higher. In this case, the risk has eventuated and the Aboriginal groups protest against the design. You now have to pay $20,000 to Aboriginal consultants to manage these dissatisfied stakeholders. You lose 10 marks.

Note: Under a good risk management plan, extreme, high, and moderate risks must be actively managed.

After reflecting on this feedback, the players move onto the next phase of the project.

Implications and conclusion

This paper presents on an action research study designed to interactively engage students in project risk management learning. The major contribution of this research in adopting online game in teaching and learning are twofold:

- The pedagogical design of project risk management is a generic methodology, which means it can be applied to different disciplines. It will be implemented first Spatial Sciences and Construction units, but scenarios are under consideration for others such as chemistry and health. A scenario template has been developed for educators to follow.

- A comprehensive assessment framework has been developed. The activity log can trace students' decision-making process, which provides valuable information for teaching and learning. Immediate feedback provided to students after each risk decision is made can improve students' learning performance in following. Further, the self-assessment at the end of the game is designed to help students review and reflect upon their own learning outcomes and skills in a constructive way. Therefore, they will become more effective, confident and independent learners.

The next actions for this project are to use Simsoft in two units in the first semester of 2012 and to develop more scenarios. In particular, we want to get students involved in designing their own scenarios in order to test their risk management skills. We will also encourage educators from other disciplines to design their scenarios using our template and engage their students in this interactive game.

References

Abt, C. C. (1970). Serious games. New York: The Viking Press.

Bloom, B. S., Masia, B. B., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals (Handbook I: Cognitive Domain). London: Longman.

Caillois, R. (1961). Man, play and games (M. Barash, Trans.). New York: Free Press of Glencoe.

Carroll, J. M. (2000). Making use: scenario-based design of human-computer interactions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Costikyan, G. (2005). I Have No Words & I Must Design. In K. Salen & E. Zimmerman (Eds.), The Game Design Reader (pp. 192-211). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Eldredge, D. L., & Watson, H. J. (1996). An Ongoing Study of the Practice of Simulation in Industry. Simulation & Gaming, 27(3), 375-386. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1046878196273008

Faria, A. J. (1987). A Survey of the Use of Business Games in Academia and Business. Simulation & Games, 18(2), 207-224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/104687818701800204

Faria, A. J. (1998). Business Simulation Games: Current Usage Levels - An Update. Simulation & Gaming, 29(3), 295-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1046878198293002

Faria, A. J., & Wellington, W. J. (2004). A Survey of Simulation Game Users, Former-Users, and Never-Users. Simulation & Gaming, 35(2), 178-207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1046878104263543

Hubbard, D. W. (2009). The Failure of Risk Management. New Jersey: Wiley.

McKenna, R. J. (1991). Business Computerized Simulation: The Australian Experience. Simulation & Gaming, 22(1), 36-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1046878191221003

Michael, D., & Chen, S. (2005). Serious games: Games that educate, train, and inform. Boston: Thomson Course Technology PTR.

Prensky, M. (2007). Digital game-based learning. St. Paul, Minnesota: Paragon House Publishers.

Project Management Institute (2006). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (3rd edition). Newtown Square, Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute.

Rahat, I., & Peter, E. (2005). Scenario based method for teaching, learning and assessment. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 6th conference on Information technology education, Newark, NJ, USA.

Schrage, M., & Peters, T. (1999). Serious play: How the world's best companies simulate to innovate. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Standards Australia. (2009). Risk management. AS/NZS 31000:2009. Sydney, NSW.

Suits, B. (1967). What is a game? Philosophy of Science, 34(2), 148-156. http://www.jstor.org/pss/186102

Suits, B. (2005). Construction of a definition. In K. Salen & E. Zimmerman (Eds.), The game design reader (pp. 172-191). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Tidwell, J. (2005). Designing interfaces. Sebastopol, California: O'Reilly Media.

| Please cite as: Xia, J. C., Caulfield, C., Baccarini, D. & Yeo, S. (2012). Simsoft: A game for teaching project risk management. In Creating an inclusive learning environment: Engagement, equity, and retention. Proceedings of the 21st Annual Teaching Learning Forum, 2-3 February 2012. Perth: Murdoch University. http://otl.curtin.edu.au/tlf/tlf2012/refereed/xia.html |

Copyright 2011 Jianhong (Cecilia) Xia, Craig Caulfield, David Baccarini and Shelley Yeo. The authors assign to the TL Forum and not for profit educational institutions a non-exclusive licence to reproduce this article for personal use or for institutional teaching and learning purposes, in any format, provided that the article is used and cited in accordance with the usual academic conventions.

[PDF version] [Refereed papers] [Contents - All Presentations] [Home Page]

This URL: http://otl.curtin.edu.au/tlf/tlf2012/refereed/xia.html

Created 22 Jan 2012. Last revision: 22 Jan 2012.